Notifications

7 minutes, 52 seconds

-5 Views 0 Comments 0 Likes 0 Reviews

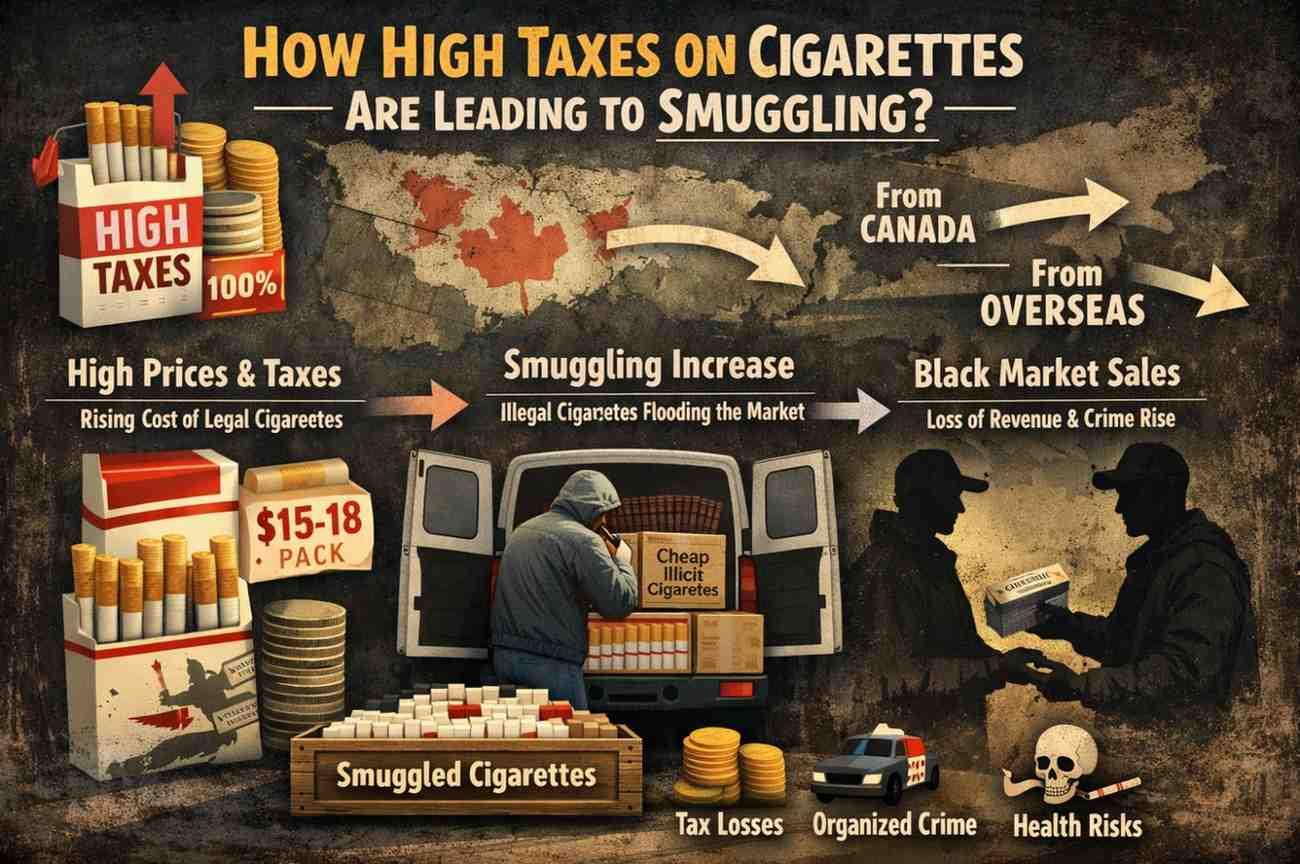

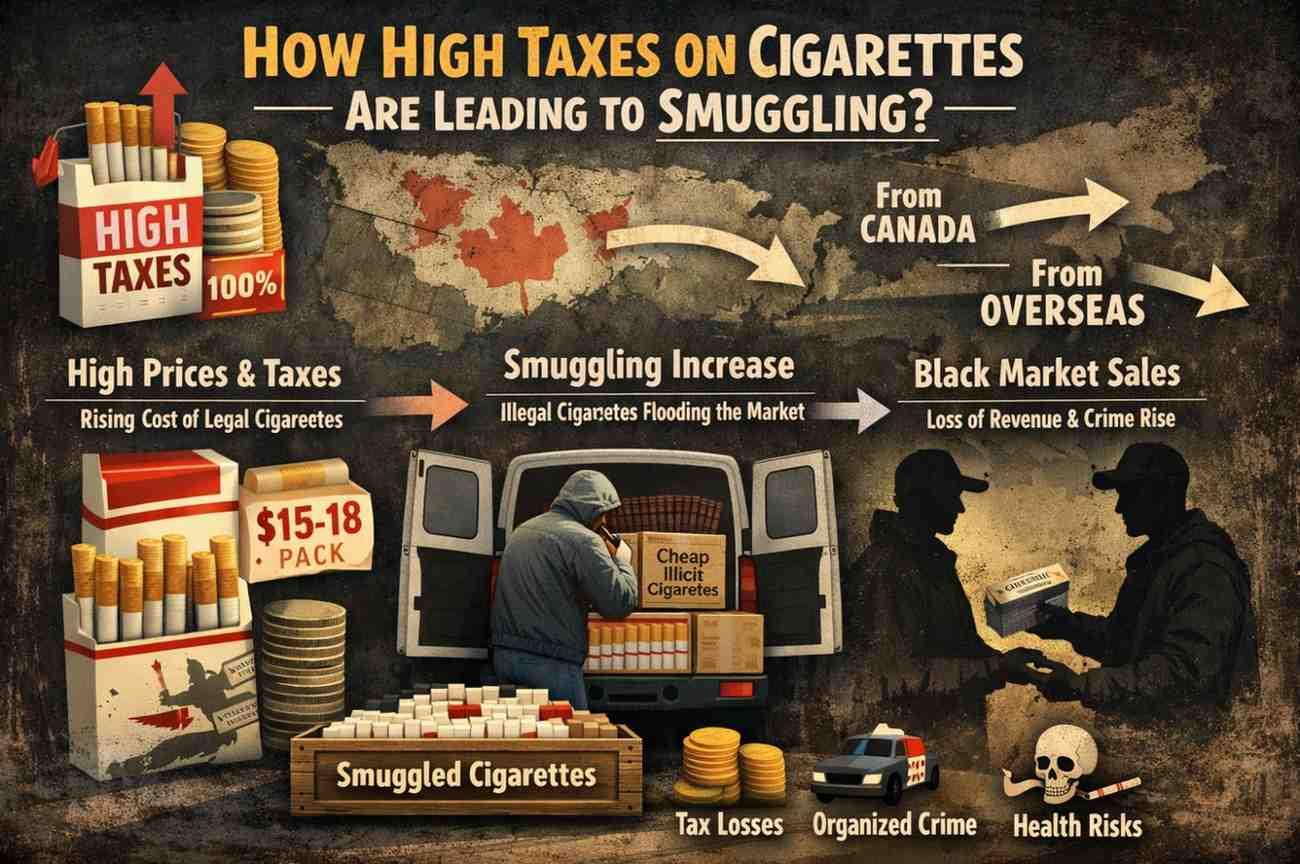

In Australia, cigarette prices have soared to among the world's highest, with a single pack now costing over $50 in many states. This surge stems directly from aggressive tobacco taxation policies introduced over the past decade, aimed at reducing smoking rates and funding public health initiatives. Governments have hiked excise duties annually, pushing the average price per pack to exceed AUD 40-50, depending on the brand and location. While these measures have contributed to a decline in legal tobacco consumption, they have also unleashed an unintended consequence: a booming black market for smuggled cigarettes. Criminal networks exploit the vast price gap between legitimate sales and illicit imports, flooding streets with cheap, unregulated products. This not only undermines tax revenue but also poses serious health and safety threats to consumers who unknowingly purchase dangerous counterfeits.

Australia's tobacco tax regime is one of the strictest globally. Since 2010, the federal government has implemented annual indexation of excise taxes, tied to Average Weekly Ordinary Time Earnings (AWOTE) plus a 2.5% tobacco-specific increase until 2023, after which it shifted to CPI indexation with additional hikes. By July 2023, the excise on a standard pack of 25 cigarettes reached AUD 1.564 per stick, totalling around AUD 39.10 per pack before GST and retailer margins. In high-tax states like South Australia and Tasmania, retail prices climb even higher, often surpassing AUD 55. These figures dwarf prices in neighbouring Southeast Asian countries, where a comparable pack sells for under AUD 5. This disparity creates a lucrative incentive for smugglers, who can buy tobacco cheaply abroad and sell it domestically at a premium, pocketing massive profits with minimal risk compared to other illicit trades.

Economic theory supports this outcome. Basic supply-and-demand principles, combined with the Ramsey rule of optimal taxation, suggest that high excises on addictive goods like cigarettes can work until a tipping point. When taxes push prices too far above consumers' willingness to pay, black markets emerge as rational responses. A 2022 study by the University of Queensland's Centre for Business and Economics of Health quantified this: for every 10% price increase from taxes, illicit trade rises by 5-7% in high-income countries like Australia.

As per World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates globally, 11.6% of cigarettes are smuggled, but in Australia, independent audits peg the figure at 15-20% of total consumption. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) reported seizing over 100 tonnes of illicit tobacco in 2023 alone, valued at AUD 150 million in lost excise, yet this captures only a fraction of the problem.

Smuggling operations have evolved into sophisticated enterprises. Syndicates source cigarettes from low-tax havens like Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Eastern Europe, often disguising them in shipping containers labelled as tea, clothing, or electronics. Small-scale "chop-chop" tobacco, loose and unregulated, dominates urban black markets, sold via street vendors, tobacconists, and even online. In Sydney's suburbs and Melbourne's outskirts, plain-paper packs without health warnings sell for AUD 20-30, undercutting legal cigarettes in Australia by half. Organised crime groups, including biker gangs and international triads, control much of this supply chain, using profits to fund other illegal activities. A 2021 Australian Federal Police (AFP) operation dismantled a network importing 50 million sticks annually, highlighting the scale. These groups evade border controls through misdeclaration and corruption, with the Australian Border Force (ABF) noting a 30% rise in detections since 2020.

The consequences ripple far beyond lost revenue, which the ATO estimates at AUD 1-2 billion yearly. Public health suffers most acutely. Illicit cigarettes often contain higher levels of toxins, heavy metals, and contaminants due to poor manufacturing. A 2019 study by the University of Sydney found that chop-chop samples had 2-3 times more tar and nicotine than regulated brands, plus traces of pesticides and rat feces. Without quality controls, they increase risks of cancer, heart disease, and respiratory issues, ironically countering anti-smoking campaigns. Vulnerable groups, including low-income smokers in regional areas, bear the brunt, turning to these cheaper but deadlier alternatives to cope with tax burdens.

Communities face broader harms too. Smuggling fuels violence, with turf wars leading to arson attacks on legit retailers, as seen in a 2022 Queensland tobacconist firebombing spree linked to debt disputes. Small businesses lose sales, and tax dollars meant for hospitals and schools vanish into criminal hands. Enforcement strains resources: the ABF and state police divert funds from other priorities, while courts backlog with minor possession cases. Every day Australians encounter this crisis at fuel stops, markets, and social gatherings, where the temptation of bargain smokes proves hard to resist amid rising living costs.

Efforts to combat smuggling include track-and-trace technologies mandated under the Illicit Tobacco Offences Act 2019, requiring unique markings on legal packs. International cooperation via Interpol and ASEAN agreements has led to joint busts, and public awareness campaigns urge reporting suspicious sales. Yet, these measures treat symptoms, not the root cause: punitive taxes that price legal smokers out of the market.

A balanced approach is essential. Policymakers could consider moderating annual increases, perhaps capping them at inflation rates, while bolstering legal affordability options. This would shrink the price gap exploited by smugglers without abandoning harm reduction. Retailers like My Cigs Australia play a vital role here, offering competitive pricing on compliant products to keep consumers in the legal fold.

Ultimately, while high taxes have cut smoking prevalence to historic lows of 8.3% in 2022 per the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare study, the smuggling surge demands recalibration. Ignoring it risks a shadow economy that endangers health, erodes trust in government, and empowers criminals. By addressing tax-induced distortions humanely, Australia can protect its citizens more effectively.